Eric Webb

Managing Consultant

By Eric Webb, Managing Consultant and Duncan Anderson, Consultant

Mediation is a non-binding ADR process that allows the parties to retain control and resolve issues without recourse to expensive and lengthy formal processes. Eric and Duncan share their thoughts on the tactical use of mediation, the associated case law and how mediation can be used as part of a dispute avoidance strategy.

Managing Consultant

Consultant

Mediation is a “flexible process conducted confidentially in which a trained neutral mediator actively assists people and/or organisations to work towards a negotiated agreement of a dispute.” [1]

Unlike other forms of dispute settlement, mediation is a non-binding alternative dispute resolution (‘ADR’) process whereby the parties to a dispute are facilitated by a neutral third party to negotiate a settlement in a controlled and confidential environment. Mediation in its modern form applies principled negotiation to dispute settlement and has become an integral part of ADR methods globally.

In Systech’s previous article on mediation, Mark Woodward-Smith outlined the benefits of mediation as an alternative approach to arbitration or litigation. In this article, the risks and potential consequences of not mediating in lieu of pursuing arbitration or litigation are examined with reference to recent case law. In particular, the judgment of the Court of Appeal in the Churchill case [2], in which the Court established that a court can, in principle, order litigating parties to undertake a non-court dispute resolution process prior to hearing a dispute.

Parties are free to mediate at any time, but whether mediating is the ideal form of ADR to pursue requires careful thought.

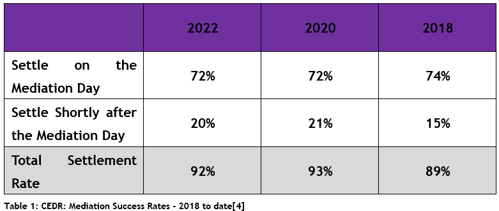

Where disputes involve complex issues, numerous separate claims and multiple parties, mediating can guide parties to resolving disputes in whole or in part. Mediation boasts a success rate of over 92% [3], meaning that four out of five cases involved in a mediation settle either at the mediation or shortly after. Resolving even one or two complex issues can save considerable costs later on if a dispute continues into arbitration.

In addition to the savings in legal costs and time spent in dispute, adopting mediation as a first avenue of ADR allows parties to retain full control over the process. Mediation is neither formal nor binding, so project teams can potentially progress matters in the interest of the project without the need for approval or involvement from central risk / legal departments.

In contrast, arbitration and litigation are formal, binding proceedings wherein the remedies applied are out of the hands of the parties and rest solely with the presiding authority. Where cost sensitivity is a shared interest by Contractor and Employer, mediation provides a faster and cheaper alternative.

Your best alternative to a negotiated agreement (or ‘BATNA’), and conversely your worst alternative to a negotiated agreement (‘WATNA’), is a key piece of information that can be used to strategize whether mediation or arbitration are more suited to your interests.

In most mediations, each party is already consciously or subconsciously thinking about their alternatives to settlement. Problems arise because parties often fail to undertake an objective and well-informed BATNA/WATNA analysis. As a result, unrealistic positions become adopted based on idealistic assumptions of what these alternatives are.

What the best and worst alternatives to a negotiated settlement are individual to each party, but often depend on certain key questions such as:

Strategy depends on preparation and a BATNA or WATNA can be a useful tool to indicate whether it is better to enter settlement discussions or walk away.

Mediation provides a means for parties to actively resolve disputes before too much money or time is spent, and unlike other forms of ADR, a skilled mediator can facilitate parties in dispute to better understand where their shared interests may lie, such as avoiding sunk costs or negative publicity.

While mediation is not mandatory, it is strongly encouraged by courts and in recent years it has become more common for parties to agree a contractual obligation to mediate before arbitration or litigation proceedings may commence. Where parties refuse to mediate, this may result in financial penalties.

Generally, in arbitration or litigation, the unsuccessful party will be ordered to pay the successful party’s costs. However, there are notable factors that may impact a court’s decision, such as a party’s conduct surrounding proceedings, and the efforts made prior to proceedings to resolve the dispute.

In Halsey, the Court of Appeal established the principle that a successful party may be penalised in costs if it unreasonably refuses to participate in ADR. It noted that any decision to deprive a successful party of any of its costs on those grounds is an exception to the usual rule that costs follow the event.

In Halsey, the following non-exhaustive list of considerations was identified to assist in determining whether a party acted unreasonably in refusing to mediate, these are commonly known as the Halsey principles:

1. The nature of the dispute,

2. The merits of the case,

3. Other settlement options,

4. Costs of mediation,

5. Delay,

6. Prospects of success, and,

7. Other factors including judicial encouragement, whether further expert evidence is required, and the impact of a Part 36 offer (an early offer for settlement).

In Churchill, it was held that the court can lawfully stay proceedings for, or order parties to engage in ADR – provided that the order does not (1) impair the essence of the claimant’s right to a judicial hearing, and (2) is proportionate to the legitimate aim of settling the dispute fairly, quickly and at reasonable cost.

Finding itself to not be bound by Halsey to refuse a stay of proceedings, this decision represents a turning point for ADR in all forms: the courts now have the power to stay proceedings and make an order compelling parties to participate in any suitable form of ADR process, at whatever stage of the proceedings considered appropriate.

Whether it is reasonable or not to refuse to mediate will differ on a case by case basis, however what is clear is that a skilled mediator will always have a chance of helping parties to resolve their dispute at lesser cost; and, in light of recent case law, it is clear that the benefits of adopting mediation will, more often than not, outweigh those of simply pursing arbitration / litigation at the earliest opportunity.

In summary, incorporating mediation into business practices is not just for dispute resolution; it is a strategic move aimed at proactively avoiding disputes. By prioritizing open communication and collaborative problem-solving, mediation becomes an essential tool for fostering a constructive working environment.

If you are looking to integrate mediation into your project strategy, our team is ready to support you. Contact us to find out how we can help you adopt a proactive approach to dispute avoidance.

[1]See Centre For Effective Dispute Resolution (Cedr), ‘What Is Mediation?’, [Https://Www.Cedr.Com/Commercial/]

[2]Churchill V Merthyr Tydfil Cbc [2023] Ewca Civ 1416.

[3] Centre For Effective Dispute Resolution (Cedr), The Tenth Mediation Audit, Dated 1 February 2023, P.7.

[4]Ibid.